Many things impressed me during my week–long ART LAB residency. The first half of our experience at the B2 Institute taught me about the quiet urgency of invasive species coupled with drought and imminent climate change in the southwest. Scientists Sujith Ravi, Greg Barron-Gafford and Lindsay Bingham imparted their knowledge about these issues: how native plants have adapted the use of open spaces between them to balance their use of resources and prevent widespread fire damage, and how now Buffle Grass creates connectivity between these—when burning it can travel the length of a football field in 3 minutes flat, destroying native vegetation forever.

Scientist Yoost Van Haren led us on an enthusiastic and insightful tour inside the biosphere, where we learned about many experiments that aim to study these problems in the desert and others ecosystems beyond. Inside B2 I found the powerful loud fans unsettling, but interesting—the fans are placed throughout B2 in order to aid the trees—which must be lifted up with harnesses as there’s not enough natural wind to develop the strength to support their own weight. It made me think of the lack of native sounds in B2 as well. What happens to a tree without participatory insects and birds or even other species? Aside from the lack of physical wind, what happens to ecosystems with a lack of auditory phenomena? I thought of installing speakers inside the Biosphere with recordings of autochthonous sounds to see if it would be possible to measure any changes over time.

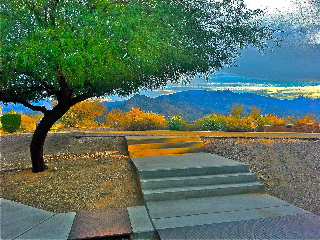

During the second half of ART LAB we were guests of Valer Austin at lovely El Coronado Ranch where we saw first hand how it is possible to restore landscapes that have been scarred with over grazing and poor management, ending the week with a hopeful and inspiring picture. The first afternoon and evening we gathered around the patio with biologist Yar Petryszyn to study a collection of mammal skulls and learn about bats. While seated in a circle passing around skulls a number of honeybees kept aggressively buzzing around and landing on me, making me feel a bit wary. Having kept bees for a season I was surprised by my unease around them. “They’re just honeybees! Why so anxious?” I asked myself. The next day along our walks studying gabbiones and trincheras, Valer stopped to show us a few native pollinator plants that were beginning to take seed and described the importance of disseminating information about planting and preserving seeds on both sides of the border. She impressed upon us the variety of pollinators, pollinator plants and seed dispersal methods, and reported that on her land alone there are estimates of 450 native bee species—quite a number indeed!

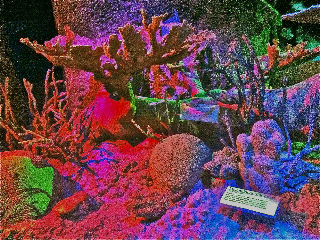

By the end of our stay at the ranch I felt inspired to assist Valer in getting the word out about these pollinators and plants. But I also felt in awe of the sheer numbers of native bees. I remembered I read somewhere an estimate that the Sonoran Desert has over 1,000 species of native bees, making it one of the most diverse bee population in the world. Back home in Tucson, I decided to meet with a few native bee experts to learn more about native bees. UofA insect behavior researcher Jennifer Jandt and native bee researcher and coordinator of Pollinator Partnership Stephen Buchmann confirmed what I remembered and informed me that the largest threat to native bees is not lack of pollen or plants due to grazing or invasive species, but competition from—HONEY BEES! This surprised me and made me remember those pestering bees back at the ranch. My plan now is to create an installation about native bees that will include a bi-lingual take-away pamphlet about native pollinators and their plants that Valer can use apart from my project.